Bootstrapping

I’ve had to setup 3 different macbooks from scratch recently, and it made me think of the whole process of Macbook bootstrapping. It’s something I’ve done a fair few times over the years, either because I’ve change jobs, get a new personal Macbook or, as is the case recently, had to nuke a work laptop back to factory settings and start again after a buyback program.

It lead me to think about my experience with developer bootstrapping in the OSX world, and realising it’s now been over a decade of experiencing the aches and pains and eventual improvements to this experience. I thought I’d do a small braindump of my experiences and the various tools we used and what I use now.

Cliffnotes OSX Bootstrapping History

When I was a fresh-faced new engineer (way back in 2011), my first proper onboarding experience was a mix of scripts and crusty wiki pages that I was manually going through . I’d literally never touched a Macbook before and I think it took me almost 2 weeks to get my machine to a point where I could even run a basic version of the full stack for the platform.

I was at a company that was slap-bang in the middle of going through a number of huge transformations, but the main application I was working on was a legacy Java app that was due to be deprecated sooner rather than later. This lead to a bit of a catch-22 where the scripts to get it up and running were fairly creaky, but also the team didnt think it a good use of time trying to fix and improve the bootstrap process.

Eventually I got through the bootstrapping and got a working machine, but the pattern continued with other new joiners, although things were simplified when the original app had been fully deprecated and turned off.

The biggest challenge that comes with bootstrapping OSX is that it’s a bit of a frankenstein. both an OS based on unix and BSD, as well as a walled garden OS that doesn’t seem to want you mucking around with the internals too much.

In practical terms, the biggest issue is a lack of native package manager. Ports was originally made to fix this problem way back in 2002, but homebrew seems to have become the new default since it’s release.

Enter Boxen

Around 2013 Github open-sourced their internal project used to manage their OSX machines: Boxen. It was a combination of Puppet, Homebrew, custom modules and bootstrapping as an solution to setup machines. You had pre-made modules to configure some of the most popular applications out there, plus the Boxen team had done some heavy lifting by creating pre-made compiled versions of things like Ruby.

By this point, I’d moved from App Support to the Operations team, and had recently learnt Puppet as part of our new devops approach, and I was on my way into the world of infrastructure as code.

Since I was one of the Puppet SME’s, I was tasked with getting Boxen up and running and we rolled it out to all the developers over a few weeks.

For the broad strokes it did what it said on the tin: allowed the use of centralised reusable modules, installed the correct baseline applications specifiied and setup config files. This was a huge boon for us as an ops team, and getting this part working allowed us to delete vast amounts of unmaintained wiki pages and scripts that no-one really understood.

Boxen Challenges

The problem was, a lot of the core concepts of Config Management don’t grok well with a user managed end device. Config Management tools expect to be the single source of truth, users don’t want any changes they’ve made being stomped over the next time a Puppet run happens.

There was also the complexity. When things went wrong, the errors required two areas of domain expertise: Not just Puppet but the excentricities of Boxen itself, as it did a lot of monkeying under the hood of Puppet to do OSX specifics.

There were also issues when it came to something relatively simple like installing a new release of a package.

Lets give an example of the Boxen module I have for installing smcfancontrol.

The Puppet code is pretty simple:

# smcfancontrol class

class smcfancontrol {

package { 'smcfancontrol':

ensure => 'installed',

provider => 'compressed_app',

source => 'https://dl.dropboxusercontent.com/u/83828942/smcFanControl-2.4.tar.gz';

}

}

So we are working around the lack of a native package manager for OSX by having a Boxen specified compressed_app provider that fetches a remote compressed artifact and then extracts it to the /Applications/ path.

So, every time a new version of the application was released, you’d have to open a pull-request to update the source parameter, then release a new version of the module and then fetch that into your Boxen setup. It also meant that doing rollbacks or removing applciations was extremely difficult.

Technically, neither of these issues was Boxen or Puppet specific, it was a symptom of the lack of a native package manager for OSX. Regardless,

Brew Cask

A huge boon for Boxen was the development of the “Cask” feature for Homebrew.

Homebrew had a bit of a philosophical idea it should only be used to install things that were fully built from source from the command line. But then actually installing OSX applications themselves via DPKG or DMG packages was deemed out of scope, even though it technically could be done inline within a brew formula.

Boxen did come with Puppet module for a brewcask provider. This meant we could leverage the same smoother package managed installation of applications within Puppet.

This means you went from:

class smcfancontrol {

package { 'smcfancontrol':

ensure => 'installed',

provider => 'compressed_app',

source => 'https://dl.dropboxusercontent.com/u/83828942/smcFanControl-2.4.tar.gz';

}

}

to

package { 'smcfancontrol':

provider => 'brewcask'

}

We’re pushing all the heavy lifting of the ongoing management of smcfancontrol onto the package manager itself. You’d still have to do the same things as before when it came to things like upgrade (go into the Brew formula, update the URL when a new version came out etc) but we’re now moving that into the package manager, and also there was a community list of Casks that people had made so a lot of the time you didn’t even have to do it yourself.

Boxen Usage

Boxen did improve over time, and after leaving my role where I first implemented it, I continued to use it at organisations afterwards. One of the government projects I worked on involved a lot of convoluted SSH tunnel configuration, config files and hacking of /etc/hosts files as a poor-mans-DNS.

Whilst a lot of the developers had the same struggles when Boxen went wrong, simply implementing all of the VPN, SSH tunnel various system level settings in Puppet rather than shell scripts and README files was a massive. Onboarding went from weeks to days to hours.

However the overriding issue was that if it went wrong, it was me people came to come fix it, and most of the time the solution was just “Oh it’s error’d but it’s actually fine!” or “Just run boxen again, that should fix it.

Joining Puppet

In 2015 I ended up joining Puppet as a company. I was working as a Pro Services Engineer and later a Technical Account Manager, so I was less involved in the nitty gritty of internal operations, but various teams within Puppet did use Boxen for machine setup, including the Education team. In fact, they still have a Boxen repo out there.

Enter Strap

It turns out, the issues around complexity in debugging Puppet and a tendency to have to just run it a few times before it works were actually being shared by the place that created Boxen in the first place.

Mike Mcquaid was working at Github and noticed the same issues:

In my experience maintaining Boxen none of these requirements held true. Users expected to be able to able to install random software with Homebrew and random versions and not have it interfere with Boxen, they wanted to be able to customise configuration in a way that Boxen disagreed with, they found Boxen’s output confusingly non-actionable and flaky internet connections and Puppet logic meant that “rerun boxen” was the best way to fix problems.

He tackled this head-on and came up with an paired down solution: Strap.

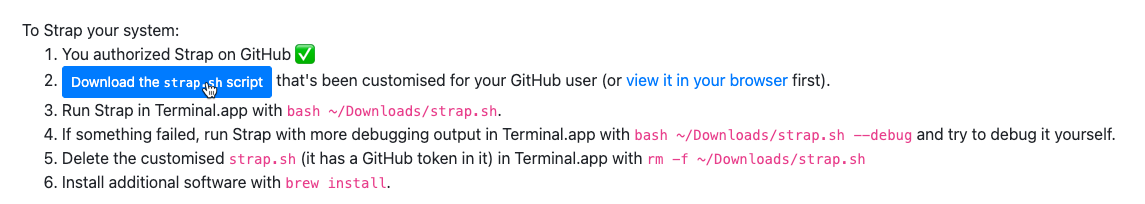

Strap basically reduced the complexity of Boxen overall by pairing it down to it’s bare essentials: - The minimal bootstrapping needed to allow the installation of homebrew (xcode CLI tools, setup git credentials to allow cloning etc) - Install homebrew - Fetch the users specific dotfiles and scripts they have control over and run them - Install a list of brew packages specific to the end user from a brewfile

With Strap, there was no hard dependency on Puppet, users could easily leverage their existing dotfiles and scripts, and the applications they needed to be installed could be listed at the user or project level with Homebrew Brewfiles.

This would’ve been fine as a vanilla shell script that required some tweaks, but one of the neat features was Strap had a small Sinatra app that would tie into Github’s API.

So in one-click you’d give it permissions to create you a new API key that it would add to the script, and this meant that if your dotfiles or brewfiles were private, you wouldn’t have to configure your authentication before you started your bootstrapping process.

You then just download the strap.sh script, run it and you’re off!

My Personal Bootstrapping Checklist

Since 2016, I’ve now done a full from factory new bootstrap on almost a dozen macbooks, either my own or assisting others. Like any software and ecosystem, things do shift over time, and it’s never a completely frictionless experience but I’d say it’s as close to a seemless exprience as you could ever get.

Here’s my documented steps of what I do, both to explain my experience and honestly, to help remind me when I inevitably have to do this again or recommend an approach for someone else doing a new OSX setup.

Install 1Password.

Theoretically I could log into Github by manually typing my password from memory, and then wait for 1Password to be installed by homebrew. But ultimately things go a lot more smoothly if I just have 1Password from the jump, especially since some of my MFA codes are going to be in there as well.

Install Rectangle.

Rectangle is a window manager for OSX that allows you to move applications around your screen with keyboard shortcuts. I’ve found I often go an manually install it from the website before I bootstrap as I’m so conditioned to moving windows with it at this point that it’s a pain moving application windows around manually. Rectangle I think is the 2nd or 3rd iteration, previously I used SnagIt and

Click the “Authorize Strap” button on Github

I think technically I don’t even need to do this, as all of my relevant repos are public, so there’s no need for authentication, but it probably helps with rate-limits and honestly, its two extra clicks so it’s not a huge deal.

Download and Run Strap

bash ~/Downloads/strap.sh and we’re off to the races!

From here, Strap will do a 6 things:

- Set some baseline system level settings (Enable Full Disk Encryption, Force Screensaver with Password, adds “Found this computer?” message to login scren etc)

- Install the minimal requirements to install homebrew: Xcode Command Line Tools and agreeing to it’s license

- Configure git to use the API token from the script for authentication

- Download and install Homebrew itself

- Fetch and run dotfiles (if available) from

https://github.com/$STRAP_GITHUB_USER/dotfiles - Do a Brew install against a brewfile from

https://github.com/$STRAP_GITHUB_USER/homebrew-brewfile

First teethings… Dotfiles

Generally, the first point of friction I’ve found is running the dotfiles. I’m old school, I still use vanilla bash over anything cool like zsh or fish, and my dotfiles have been at my side since 2010 and they’re comfie for me.

./script/bootstrap

[ ? ] - What is your github author name?

[ ? ] - What is your github author email?

[ OK ] gitconfig

[ OK ] skipped /Users/peter.souter/projects/dotfiles/golang/golang.symlink

[ OK ] skipped /Users/peter.souter/projects/dotfiles/bash/inputrc.symlink

[ OK ] skipped /Users/peter.souter/projects/dotfiles/bash/bashrc.symlink

[ OK ] skipped /Users/peter.souter/projects/dotfiles/bash/prompting.symlink

[ OK ] linked /Users/peter.souter/projects/dotfiles/bash/completion.symlink to /Users/peter.souter/.completion

[ OK ] skipped /Users/peter.souter/projects/dotfiles/bash/after_bash.symlink

[ OK ] skipped /Users/peter.souter/projects/dotfiles/bash/before_bash.symlink

[ OK ] skipped /Users/peter.souter/projects/dotfiles/aliases/terminal.symlink

[ OK ] skipped /Users/peter.souter/projects/dotfiles/ruby/gemrc.symlink

[ OK ] skipped /Users/peter.souter/projects/dotfiles/ruby/irbrc.symlink

[ OK ] skipped /Users/peter.souter/projects/dotfiles/git/gitconfig.symlink

[ OK ] skipped /Users/peter.souter/projects/dotfiles/git/gitignore.symlink

All installed!

I’ve had issues where there’s clashes between ENV settings that I’m configuring in there, including Github API tokens and the rest of the process, so I think this has mostly been saved now I’ve paired it down to it’s basics.

My dotfiles expect a lot of user response when bootstrapped, so I have to remember to hit the prompts before I go get coffee and let brew do it’s thing.

Next painpoint… Brewfiles

Brewfiles are basically bundler for brew, it gives a list of things to go fetch and install. Since I’ve been using strap for a while, there’s probably a bunch of cruft in there that I probably don’t need, and as the seasons change, tools and apps get deprecated, change names or become unsupported on newer versions of OSX (or even new chipsets now the M1 macbooks are out).

Warning: 'ec2-api-tools' formula is unreadable: No available formula with the name "ec2-api-tools". Did you mean ec2-ami-tools?

Warning: No available formula with the name "ec2-api-tools". Did you mean ec2-ami-tools?

==> Searching for similarly named formulae...

==> Formulae

ec2-ami-tools

To install ec2-ami-tools, run:

brew install ec2-ami-tools

Installing ec2-api-tools has failed!

It’s generally not too big of a deal, as homebrew continues on regardless of errors, but it’s something to look back on and troubleshoot at the end. The easiest solution is generally just purging the problem-child apps from the list, but if you actually need them.

Once that’s all done, you’ve got the broad strokes of a machine and I can generally get down to business on most of my day-to-day development or general activities.

What’s left?

The last few bits are a bit fiddly and security related: Git, GPG, SSH and Commit Signing. Basically things that are impractical to automate to a certain degree, or I just haven’t got around to automating more yet.

Github HTTPS authentication

If you want to clone Github HTTPS urls and you have MFA enabled, you need to configure git to use an API key instead of a password. This process used to be a bit finicky with the standard osxkeychain approach. You’d need to login to Github, create an API key with the right permissions, then do a git command that required authentication over HTTPS and enter the API key instead of your normal password.

This process has been hugely improved with gcm: git-credential-manager. Essentially it automates the whole process so you can do everything from the command-line, have a prompt open a browser to enter your MFA key (which is useful for me as my MFA credentials are in 1Password so it’s a one click process) and it’ll do all the work behind the scenes to configure that.

SSH Config Tinkering

I use SSH on a daily basis, both at work and in my personal life. There’s a bunch of sensible default configuration I want to setup in my ~/.ssh/ssh_config during the bootstrapping process. Previously I’d do an entire Puppet setup and use something like the augeus provider to configure things, but honestly I’ve not really touched used Puppet seriously for several years now and it’s a pretty hefty tool to use to configure just one file.

I did some work originally creating a Terraform provider to do this, but since I first started working on it Terraform has massively changed how they do provider development, there’s a bunch of package upgrading I need to do and I just didn’t have the energy to do all that. Someday I might get back to it, as it would be a cleaner approach.

What I did end up doing is one of my favourite development hobbies: creating a little CLI tool that has a very specialised task for my requirements. In this case, configuring ssh_config files on the command-line without overwriting previous configuration.

I’d already forked and build on a go-sshconfig library that I’d used in the initial work for the Terraform provider, so I’d already got a lot of the logic working, and I’ve fallen in love with using golang for self-contained CLI tools because of the ease of packaging (especially compared to my previous experiences with Ruby and gems) and the amount of well-supported libraries and CLI usecases.

Enter: sck

It’s pretty simple, you give it some CLI parameters and it’ll add the new parts to your existing configuration. It has some fancy tricks around doing dry-runs and backing up the original file, but at it’s heart it does on specific job and does it very well.

$ sck host -h github.com --param IdentityKey --value '~/.ssh/foo-bar-baz' --dry-run

New SSH Config:

# global configuration

# host-based configuration

Host github.com

IdentityKey ~/.ssh/foo-bar-baz

I’ll probably end up blogging about SCK and some of my other golang CLI applications I’ve made, especially around how I’ve been acceptance testing it with tools like Aruba.

SSH Key Generation and Deployment

The general recommendation is to avoid migrating existing SSH private keys from old machines to a new one. Instead you should generate new ones and then change your public keys on the remote servers to match the newly generated keys.

Generating the keys I generally do on the command line, but I did write some Terraform to do it in the past:

provider "github" {

individual = true

}

data "external" "todays_date" {

program = ["sh", "-c", "echo \"{\\\"date\\\" : \\\"$(date +\"%d_%b_%Y\")\\\"}\""]

}

locals {

current_date = "${data.external.todays_date.result.date}"

filename = "github_ssh_key_${local.current_date}"

}

resource "tls_private_key" "github_key" {

algorithm = "ECDSA"

ecdsa_curve = "P384"

}

resource "local_file" "github_private_key_local" {

filename = "${pathexpand("~/.ssh/")}/${local.filename}"

sensitive_content = chomp(tls_private_key.github_key.private_key_pem)

file_permission = "0600"

}

resource "local_file" "github_public_key_local" {

filename = "${pathexpand("~/.ssh/")}/${local.filename}.pub"

content = chomp(tls_private_key.github_key.public_key_openssh)

file_permission = "0600"

}

resource "github_user_ssh_key" "macbook_github_date" {

title = "Personal MacBook Air - ${local.current_date}"

key = chomp(tls_private_key.github_key.public_key_openssh)

}

output "ssh_key_path" {

value = local_file.github_private_key_local.filename

}

output "github_ssh_configfile" {

value = <<EOT

Host github.com

ControlMaster auto

ControlPath ~/.ssh/ssh-%r@%h:%p

ControlPersist yes

User git

IdentityFile ~/.ssh/${local.filename}

EOT

}

output "test_ssh" {

value = "You can now run `ssh -T git@github.com` to test the ssh setup is correct"

}

A few of these machines are multi-tenant servers I use to host my Plex server and other bits and bobs, so those I generally have password access to. That makes adding new public keys easy, you can simply use “ssh-copy-id” to add them to the remote host, and it’ll prompt you for the password and then copy the key over when it’s done.

Other machines, it’s a mixed bag. It’s either something work related, where there’s generally some sort of config management or CMDB where I need to go update to my new public key (often in Puppet or Terraform).

Signing Git Commits

If you want to have your commits in git have a shiny “Verified” badge, you need to sign your commits with a gpg key.

Mini Rant About GPG

However, unlike ssh keys, you’re generally expected to keep GPG keys in perpetuity to prove it was you who signed things. This has always been a bit of a pain to do, but it is useful to learn as GPG/PGP is basically the main way any sort of signing and verification is done out there.

For me, I wanted a middle point: an easy way of managing my GPG keys in-perpetiuity whilst not making too many compromises on security. Some hardliners would argue that even entrusting any sort of third party with your GPG keys is already breaking the fundamental idea of even having a signing key. I do see the argument being made here, but ultimately the alternative solutions aren’t perfect either. You’ve either got the keys living on your various developer machines, and risking losing them if they’re lost in storage from an error or disk wipe, or you’re putting it on a USB key and keeping it in a fireproof safe and hoping bitrot doesn’t kill the drive.

I think Keybase is a happy medium. You can quickly setup on a new machine using MFA login from a previously authenticated device, it automates a lot of the finicky bits that are common with trying to setup GPG/PGP. Since I’ve already added the Keybase key to my Github account, I don’t have to change anything there, I just need to grab my key that Keybase keeps and encrypts with my password and add it to my laptops GPG keychain.

I’m not going to go through the steps to get your Keybase key, add it to your GPG keychain, trust it and add it to my .gitconfig, mostly because it’s been done by other people better than I have, and generally I just google “github keybase signing commits” or go to a blog post I’ve used previously in my Chrome history like Julien Ponge’s blogpost.

Funnily enough, whilst I was writing up this blogpost I found out that Keybase were acquired by Zoom in 2020 and uhhh… looks like it was mostly an aquihire and serious development on Keybase seems to have effectively ceased.

There’s a lot of discussion on one of the issues people opened to ask them to open-source the server, and it looks like people are pointing out that bugs are still being fixed, but it’s clear that new features are not on the roadmap

There seem to be a few alternatives mentioned like keyoxide/ and keys.pub (it doesn’t bode well that one mentioned in the Hacker News comments is already dead only a few years later) but none really seem to cover all the Keybase usecases and features:

Ultimately Keybase still exists and “Just Works”™ for now, so I’m not looking to move anytime soon, but I probably should at least do some PGP 101 for my website like add in a WKD for my key on my site.

Conclusion

Hopefully you enjoyed this walk down memory lane on the history of OSX bootstrap ping, and hopefully you’ve seen the advantages of using tools like Strap to get things up and running.