Header image: https://flic.kr/p/7Lx9Kk

As someone who’s started out in dev and ended up falling into ops, a lot of my approaches are heavily influenced by what I cut my teeth on early on.

Since I started out development Ruby and Rails, I learnt a lot about Test Driven Development. In fact, even before I did Rails, I was working a little on cuke4duke, a JVM Cucumber package.

I’m a big fan of using TDD when writing Puppet code, as I think it really helps with my workflow and brings a lot of advantages.

A quick history of TDD/BDD

So the idea of test-driven-development was originally born out of one of the ideas from Extreme Programming: test-first development. It’s redsicovery is largely attributed to Kent Beck, who ‘rediscovered’ it as TDD in his 2002 book: Test Driven Development: By Example. The main difference between Test First and TDD is the intent: TDD splits the design activity into two phases, one where you design the external face of the code as a spec, then the second where you design the internal organization of the code using the minimum amount of code possible. Whereas test-first was more about the basic best practise of making sure you write tests first, TDD was about actually influencing coding and design decisions to make sure tests were easy to write also.

Test Driven Development is sumarised by the idea of the R-G-R cycle: Red-Green-Refactor

- First the developer writes a failing automated test-case that defines a desired improvement or feature (Red)

- Then they write minimum amount of code to pass that test (Green)

- You then refactor the code (Refactor)

Wait, I thought you said BDD?

BDD (behaviour driven development) is essentially TDD with more refinement. Or to put it another way “BDD is TDD done right”.

It’s abstracting away the requirements so they don’t have programmer specific language.

BDD utilizes something called a “Ubiquitous Language,” a body of knowledge that can be understood by both the developer and the customer. This ubiquitous language is used to shape and develop the requirements and testing needed, at the level of the customer’s understanding.

BDD requirements normally take this format:

As an X

I want to do Y

So I can Z

Technically, the main tool we’ll use for testing is TDD, as the output is in Puppet specific language. There have been experiments in the past to make a BDD puppet language, but rspec-puppet is the one that ended up sticking around.

TDD is still readable, but it’s not abstracted away from the language it’s written in:

$ rake spec

ruby -S rspec spec/classes/init_spec.rb

git class

should contain Package[git]

Readable output from rspec (TDD)

So for the sake of clarity, I’m going to use the term TDD for the rest of this post, but they’re essentially the same approach: writing a test that explains what you want the code you’re going to write to achieve, writing the minimum code needed to make that test pass, the refactoring the code you just wrote.

Whats needed for TDD/BDD

There are some tenants to TDD working well:

- Tests should be fast

If you expect everyone to be running this over and over in a red-green loop, they need to be quick. If the loop is blocked by waiting for a 10 minute test suite to run, you’re going to bottle-neck the development process around the tests. People often split longer acceptance tests out of the main TDD loop to help with this.

- Tests should be easy to run

If you want people to follow a new design-pattern or approach, the tests should have a low barrier to entry to run. Either a rake task to run the suite, or CI to constantly check that you’re tests are green are good at this.

- Tests should be easy to write and read

This ones a bit more contentious. With the helper tools test suites like RSpec gives you, and metaprogramming you can DRY up your specs, but that comes at the cost of making them harder to read and maintain.

Ultimatly, I’d prefer tests that are more repetitive that I can understand at a glance, than more clever and DRY that take time to undertand, but it’s more of a personal preference.

Why it’s beneficial for Puppet

So where does Puppet come in?

The main benefit of TDD is that you’re only coding what you need to. Puppet code normally has a longer feedback loop to figure out when something goes wrong:

- You might be deploying it to a number of different servers, so you might have to wait until all your nodes report back before you can see any issues that have occurred

- Depending on the size of your organisation, you might not even have multiple test environments, so you want to make sure you’re code has a level of testing on it before deployment so you don’t block others with failing manifests. In addition to this, if you’re a smaller organisation, you might not even have a test environment that fully reflects production (or in the worst case, no test environment at all!)

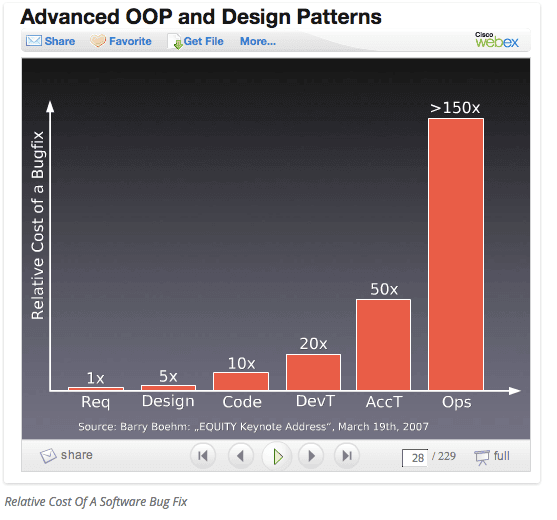

It’s common knowledge the faster bugs and problems are caught, the easier and cheaper they are to fix.

Slide credit: Barry Boehm, “Equity Keynote Address” March 19, 2007.

And this idea applies to Puppet code too. You want to catch issues as early as possible in the pipeline.

TDD generally means there’s a reduced debugging effort. When things go wrong and failures are detected, having smaller tests helps track down issues faster.

TDD is also said to be self-documenting: test cases with human-readble langague mean that someone looking at your specs should be able to determine if the code is doing what it’s supposed to and what the original itentions were.

Say I’m looking at the specs of a module, and it states that the manifest should install a certain package on RedHat 6 and 7, but it doesn’t work on RedHat 7, I know that that was in the original spec of the module, and it’s a bug that needs to be fixed.

Basic Theoretical Example of it in action

Susan comes into the office. She’s a developer who’s helping out the ops team write Puppet code and she goes to one of the teams planning sessions. There’s some discussions about lua package with Nginx. Susan says “I can help with that”. They write out a basic story and log it in Jira with the requirements:

She goes off to work on the module for the nginx installation.

Lets say the code looks something like this:

class nginx {

package { "nginx":

ensure => '1.6.0',

before => File['/etc/nginx/sites-enabled/default'];

}

service { 'nginx':

ensure => running,

enable => true,

hasrestart => true,

subscribe => File['/etc/nginx/sites-enabled/default'],

require => File['/etc/nginx/sites-enabled/default'],

}

file { '/etc/nginx/sites-enabled/default':

source => template('nginx/default.erb'),

}

}

Seems simple enough, and look, a helpful ops person before her has setup some specs! Good job guy!

$ tree spec/classes/

spec/classes/

└── nginx_spec.rb

0 directories, 1 file

Oh, but unfortunately there’s only a simple spec to see if the code compiles:

require 'spec_helper'

describe 'nginx' do

it { should compile.with_all_deps }

end

“Hmm, I think TDD might help me here. Let me define the tests with the requirements the business owners asked for me!”

So the business case is that the package needs to be the new version with the lua modules installed. So she adds a spec for that:

it { should contain_package('nginx').with_version('1.6.5-lua')}

She also needs to make sure that the nginx lua module is loaded into the config file:

it { should contain_file('/etc/nginx/conf.d/webserver.conf').with_content(/lua_package_path "/etc/nginx/app/vendor/?.lua;;";'/)}

She runs the tests and gets a fail, first step of R-G-R complete.

So she now knows to write the minimum amount of code to get the test passing:

# nginx.pp

class nginx {

package { ‘nginx’

ensure => ‘1.6.5-lua’,

}

file { ‘/etc/nginx/conf.d/webserver.conf’:

ensure => file,

content => template(‘nginx/nginx.conf’)

}

service {‘nginx’:}

}

# Load lua

lua_package_path "/etc/nginx/app/vendor/?.lua;;";

upstream webserver {

server 127.0.0.1:3000 fail_timeout=0;

}

server {

listen 80;

gzip on;

gzip_comp_level 6;

gzip_vary on;

gzip_min_length 1000;

gzip_proxied any;

gzip_types text/plain text/css application/json application/x-javascript text/xml application/xml application/xml+rss text/javascript application/javascript;

gzip_buffers 16 8k;

keepalive_timeout 5;

location / {

proxy_set_header X-Forwarded-For $proxy_add_x_forwarded_for;

proxy_set_header X-Forwarded-Proto $scheme;

proxy_set_header Host $http_host;

proxy_redirect off;

proxy_http_version 1.1;

if (!-f $request_filename) {

proxy_pass http://webserver;

break;

}

}

}

Looks like a job well done! She then sends a pull-request to be reviewed by the ops team to see if this is what they were looking for.

13:56: (Susan): Hi, mind having a look at my PR?

14:01: (Igor) : Oh shoot, forgot to say, we ended up going with 1.6.4-lua version of nginx with Lua because of compatibllity reasons

BDD is perfect for this situation! You know that if you change the spec for the package version from 1.6.5-lua to 1.6.4-lua

it { should contain_package('nginx').with_version('1.6.4-lua')}

You can just change the requirement for the package to the new version, get the red spec, change the parameter in the Puppet code, get something nice and green, and bam.

A more realistic example…

So this is a bit of a perfect example. The Puppet code is very simple and the change is fairly trivial. But this can be applied to much more complex setups, and having a clear.

So, as a professional services engineer engineer we often have to work with other peoples code. So we want to ensure that any changes we make dont break anything that was there before we started, and I have a set of tests that define what the original intnet of the manifest was.

So I was on site where someone wanted to use a new backend for hiera, and they were managing the hiera.yml file with Puppet.

So I wrote a quick spec that looked like this (variables changed to protect the innocent):

require 'spec_helper'

describe 'hiera_setup' do

context 'supported operating systems' do

['Debian', 'RedHat'].each do |osfamily|

describe "hiera_setup class without any parameters on #{osfamily} on Puppet Enterprise" do

let(:params) {{ }}

let(:facts) {{

:osfamily => osfamily,

:puppetversion => '3.6.2 (Puppet Enterprise 3.3.0)',

}}

it { should compile.with_all_deps }

it { should contain_class('hiera_setup::params')}

it { should contain_class('hiera_setup::config')}

hiera_string = <<-eos

# managed by puppet

---

:backends:

- ldap

- yaml

:logger: console

:hierarchy:

- defaults

- "clientcert/%{clientcert}"

- "environments/%{environment}"

- global

:yaml:

:datadir: /etc/puppetlabs/puppet/hieradata

:ldap:

:base: ou=puppetdata,dc=example,dc=com

:host: example.com

:port: 636

:encryption:

:method: :simple_tls

:tls_options:

:ca_file: /etc/puppetlabs/puppet/hieradata/coolcert.example.com.pem

:auth:

:method: :simple

:username: cn=ldapaccess,ou=cool servers,dc=example,dc=com

:password: hunter2

eos

it { should contain_file('/etc/puppetlabs/puppet/hiera.yaml').with_content(hiera_string)}

With this setup, I had defined what I wanted the config to look like as a string, so it was fairly easy to quickly iterate and make sure that it turned into the config I needed, without having to run Puppet over and over again.

With this I could quickly check things like parameter changes, or lookups based on Facts didn’t cause any issues to the core functionality of creating the correct hiera file.

Useful TDD Tools

Guard and Guard Notify

One of my favourite tools for TDD is Guard. Guard is basically a daemon that whats defined files from a Guardfile.

For example:

guard 'rake', :task => 'test' do

watch(%r{^manifests\/(.+)\.pp$})

watch(%r{^spec\/(.+)\.rb$})

end

This is a basic watch to run all the specs in a module, and it’ll run the rake spec task whenever it detects a change to any spec file or manifest. So then you can get quick

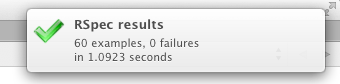

This combined with something like the many Guard notification tools out there gives you something like this:

An example of Guard notify taken from http://jam.im/blog/2013/02/11/mac-osx-notifications-with-guard/

This means your tests are constantly running in the background, and notifying you when things are green and red, speeding up your Red-Green-Refactor loop.

Beyond TDD unit-tests…TDD acceptance tests?

With Beaker, you’re not just testing your Puppet code does what it should do, you’re testing what it will do when actually executedon a real instance of your OS of choice.

The problem is spinning up a new machine is not super quick:

- Vagrant VM’s have a startup cost that makes the R-G-R loop slow

- Spinning up a cloud instance can be faster (especially if the cloud instance offers SSD nodes!) but there’s a cost associated.

One potential solution is using Beaker’s Docker support. Containers are much faster to provsion to run Puppet code on, and if setup correctly can give a fairly quick feedback loop of actual acceptance tests for your Puppet code.

I think I’ll write a post about using beaker with TDD in the future.

But for now, go an try out TDD for yourself with Puppet code, I hope it helps you in your day-to-day work!